The problem

Rain is natural. Before we built roads and buildings, it would fall on deep-rooted native plants that helped it infiltrate into the ground, to be naturally cleaned and cooled before entering the water table. As we’ve developed the landscape, we’ve also dramatically altered the path those raindrops follow. Now they fall on roofs, continue over driveways and lawns, down sidewalks, streets and other impervious surfaces. Rain turns to runoff, picking up pollutants all along the way before entering storm drains that lead to nearby bodies of water. Over half of Minnesota’s lakes, rivers, and streams are impaired, and runoff is a major contributor.

Rain is natural. Before we built roads and buildings, it would fall on deep-rooted native plants that helped it infiltrate into the ground, to be naturally cleaned and cooled before entering the water table. As we’ve developed the landscape, we’ve also dramatically altered the path those raindrops follow. Now they fall on roofs, continue over driveways and lawns, down sidewalks, streets and other impervious surfaces. Rain turns to runoff, picking up pollutants all along the way before entering storm drains that lead to nearby bodies of water. Over half of Minnesota’s lakes, rivers, and streams are impaired, and runoff is a major contributor.

A solution

Blue Thumb–Planting for Clean Water looks for solutions by mimicking the historic hydrology of undeveloped land; specifically, by helping rain filter into the ground close to where it falls, rather than running off the land and carrying pollution into the water. We can achieve this by shaping the land to divert and collect water (as in the basin of a rain garden), and covering it in deep-rooted native plants that slow down, soak up, and infiltrate runoff. This also reduces the wear-and-tear of our aging storm sewers, and helps protect low-lying neighborhoods from flooding. As we see more and stronger rains year after year, this work is only becoming more important.

The benefits of native plants

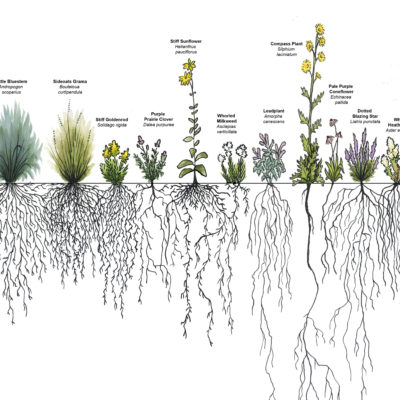

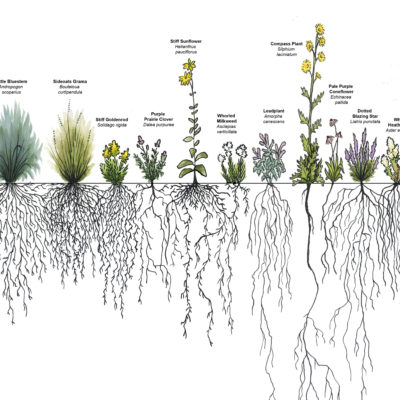

- Long-rooted native plants retain and infiltrate more water, decrease soil compaction, filter out pollutants, and sequester carbon.

- Native plants require fewer inputs (less mowing and watering, no fertilizer or pesticides), leading to lower costs.

- Native plants provide habitat for pollinators and songbirds, protecting biodiversity.

- Native plants add beauty and resilience to the landscape.

What is a native plant?

Hundreds of years ago, the United States was covered in “native” plants—the grasses, foliage, and trees indigenous to our country—before modern settlement disturbed their natural habitat. Native plants differ from non-natives because of the complex relationships they’ve developed over thousands of years with other local organisms, acting as critical components in maintaining nature’s delicate balance. Many species occurred across relatively wide ranges of geographic, climatic and environmental conditions. Sub-groups became adapted to various local conditions within these wider ranges. These are called “local ecotypes”. It is desirable to use the best adapted plants for a landscape project. Local ecotype native plants are well-adapted to local conditions. Blue Thumb projects using native plants focus on local ecotypes—plant material propagated from original sources no farther than 200 miles (300 for trees and shrubs) from the project.

Hundreds of years ago, the United States was covered in “native” plants—the grasses, foliage, and trees indigenous to our country—before modern settlement disturbed their natural habitat. Native plants differ from non-natives because of the complex relationships they’ve developed over thousands of years with other local organisms, acting as critical components in maintaining nature’s delicate balance. Many species occurred across relatively wide ranges of geographic, climatic and environmental conditions. Sub-groups became adapted to various local conditions within these wider ranges. These are called “local ecotypes”. It is desirable to use the best adapted plants for a landscape project. Local ecotype native plants are well-adapted to local conditions. Blue Thumb projects using native plants focus on local ecotypes—plant material propagated from original sources no farther than 200 miles (300 for trees and shrubs) from the project.

Native plants: resilient and beautiful

Chosen with care, native plants are hardy and able to weather harsh winters and summer heat and drought (those deep roots help!). Once established, native plants typically need less weeding, watering, mulching and mowing than other plants. There are many varieties for different soil types, light conditions and personal tastes. A native plant garden can bloom all season!

What about pollinators?

Habitat

While Blue Thumb began by using native plants to help clean water, we recognize that native plants are so much more than their deep roots. They form the base of the food web that supports native wildlife like bees, butterflies, and birds. Iconic species like the Monarch butterfly and the Rusty Patched bumble bee are threatened by the loss of habitat, but they are not alone. Just in Minnesota, many once-common pollinators are now rare or gone, primarily because they cannot eat pavement, turf grass, or corn. Around the country, we’ve lost 25% of our birds population in the last 50 years, in part because the insects they depend on are also disappearing. Native plants feed and shelter the natural world. By choosing to reintroduce them in even a small part of your yard, you can help reverse this narrative of decline.

While Blue Thumb began by using native plants to help clean water, we recognize that native plants are so much more than their deep roots. They form the base of the food web that supports native wildlife like bees, butterflies, and birds. Iconic species like the Monarch butterfly and the Rusty Patched bumble bee are threatened by the loss of habitat, but they are not alone. Just in Minnesota, many once-common pollinators are now rare or gone, primarily because they cannot eat pavement, turf grass, or corn. Around the country, we’ve lost 25% of our birds population in the last 50 years, in part because the insects they depend on are also disappearing. Native plants feed and shelter the natural world. By choosing to reintroduce them in even a small part of your yard, you can help reverse this narrative of decline.

High Quality Nectar and Pollen

Native plant flower shapes, contents, colors, and bloom times closely correspond to the biology and life cycles of the pollinators who’ve evolved with them in symbiotic relationships. Some flowers provide immune-boosting nutrients, and others are depended on to supply the protein needed by growing larvae, or the sugary nectar to keep worker bees fueled up. Many pollinators have learned to make use of introduced plants, some of which have been shown to support a wide variety of bees. Yet generally, native plants remain far and away the most promising way to support our struggling pollinators.

What’s the difference between a native plant and a cultivar?

Cultivars are plants resulting from a deliberate process to select for certain characteristics such as flower color. The word is derived from “cultivated” and “variety”. These plants are usually given a unique name. Most turf grasses, annuals and perennial bedding plants are cultivars. There are also cultivars from species native to the U.S, sometimes called “nativars”. Their genetic makeup is considered somewhat narrowed from the original source material. When we select for traits we desire (low-growing, longer bloom times, brighter colors), we may well be ending up with flowers that are less recognizable to pollinators, or that produce lower-quality nectar and pollen. We recommend using native plants as much as possible, and to only use native plants along shorelines and natural areas, where other introduced or altered plants might escape and spread.

How do I decide what to do with my yard?

What to do with your yard depends in great part on how you use it. What works in one part of a yard may be completely inappropriate in another. Many people find they have room for a native planting or rain garden and still have a lawn large enough to play or picnic on.

Factors that play a part in landscape project planning include:

- site conditions such as soil type and sun and shade;

- use requirements such as play areas or gathering spaces;

- surroundings such as shorelines, wetlands and neighborhood, cultural and other environmental elements;

- personal tastes and interests of the resident(s);

- local codes, association covenants and other requirements placed by government agencies.

Ready to make a change in your yard? Check out our Plan a Project page.

Rain is natural. Before we built roads and buildings, it would fall on deep-rooted native plants that helped it infiltrate into the ground, to be naturally cleaned and cooled before entering the water table. As we’ve developed the landscape, we’ve also dramatically altered the path those raindrops follow. Now they fall on roofs, continue over driveways and lawns, down sidewalks, streets and other impervious surfaces. Rain turns to runoff, picking up pollutants all along the way before entering storm drains that lead to nearby bodies of water. Over half of Minnesota’s lakes, rivers, and streams are impaired, and runoff is a major contributor.

Rain is natural. Before we built roads and buildings, it would fall on deep-rooted native plants that helped it infiltrate into the ground, to be naturally cleaned and cooled before entering the water table. As we’ve developed the landscape, we’ve also dramatically altered the path those raindrops follow. Now they fall on roofs, continue over driveways and lawns, down sidewalks, streets and other impervious surfaces. Rain turns to runoff, picking up pollutants all along the way before entering storm drains that lead to nearby bodies of water. Over half of Minnesota’s lakes, rivers, and streams are impaired, and runoff is a major contributor.

Hundreds of years ago, the United States was covered in “native” plants—the grasses, foliage, and trees indigenous to our country—before modern settlement disturbed their natural habitat. Native plants differ from non-natives because of the complex relationships they’ve developed over thousands of years with other local organisms, acting as critical components in maintaining nature’s delicate balance. Many species occurred across relatively wide ranges of geographic, climatic and environmental conditions. Sub-groups became adapted to various local conditions within these wider ranges. These are called “local ecotypes”. It is desirable to use the best adapted plants for a landscape project. Local ecotype native plants are well-adapted to local conditions. Blue Thumb projects using native plants focus on local ecotypes—plant material propagated from original sources no farther than 200 miles (300 for trees and shrubs) from the project.

Hundreds of years ago, the United States was covered in “native” plants—the grasses, foliage, and trees indigenous to our country—before modern settlement disturbed their natural habitat. Native plants differ from non-natives because of the complex relationships they’ve developed over thousands of years with other local organisms, acting as critical components in maintaining nature’s delicate balance. Many species occurred across relatively wide ranges of geographic, climatic and environmental conditions. Sub-groups became adapted to various local conditions within these wider ranges. These are called “local ecotypes”. It is desirable to use the best adapted plants for a landscape project. Local ecotype native plants are well-adapted to local conditions. Blue Thumb projects using native plants focus on local ecotypes—plant material propagated from original sources no farther than 200 miles (300 for trees and shrubs) from the project. While Blue Thumb began by using native plants to help clean water, we recognize that native plants are so much more than their deep roots. They form the base of the food web that supports native wildlife like bees, butterflies, and birds. Iconic species like the Monarch butterfly and the Rusty Patched bumble bee are threatened by the loss of habitat, but they are not alone. Just in Minnesota, many once-common pollinators are now rare or gone, primarily because they cannot eat pavement, turf grass, or corn. Around the country, we’ve lost 25% of our birds population in the last 50 years, in part because the insects they depend on are also disappearing. Native plants feed and shelter the natural world. By choosing to reintroduce them in even a small part of your yard, you can help reverse this narrative of decline.

While Blue Thumb began by using native plants to help clean water, we recognize that native plants are so much more than their deep roots. They form the base of the food web that supports native wildlife like bees, butterflies, and birds. Iconic species like the Monarch butterfly and the Rusty Patched bumble bee are threatened by the loss of habitat, but they are not alone. Just in Minnesota, many once-common pollinators are now rare or gone, primarily because they cannot eat pavement, turf grass, or corn. Around the country, we’ve lost 25% of our birds population in the last 50 years, in part because the insects they depend on are also disappearing. Native plants feed and shelter the natural world. By choosing to reintroduce them in even a small part of your yard, you can help reverse this narrative of decline.